The root word for labor might have meant “to slip and stumble under a heavy burden.” When the word first came into English around 1300, that evocative image had split into two distinct meanings– work and sorrow. Now, the word is mostly abstract, used in economic and political circles, but it still carries echoes of these original meanings as they have been blended together in different proportions in different usages.

For example: You might labor at something for a long time and maybe describe it as a “labor of love;” labor is a stage of childbirth; economists study labor costs and labor markets; people who do manual jobs are laborers; working people organize labor unions and politicians try to get them to vote for labor parties. Digging deeper, it turns out that a group of moles is called a labor, and the word was once a unit of land measurement in Texas (equal to 177 acres).1“Labour | Labor, n.,” in OED Online (Oxford University Press), accessed February 15, 2021, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/104732.

Each of the eleven senses listed in the OED is separate, but there is a lot of cross-talk between the meanings. Each is in the shadow of the others. They serve as metaphors for each other. And they all point to an association between work and suffering that runs deep.

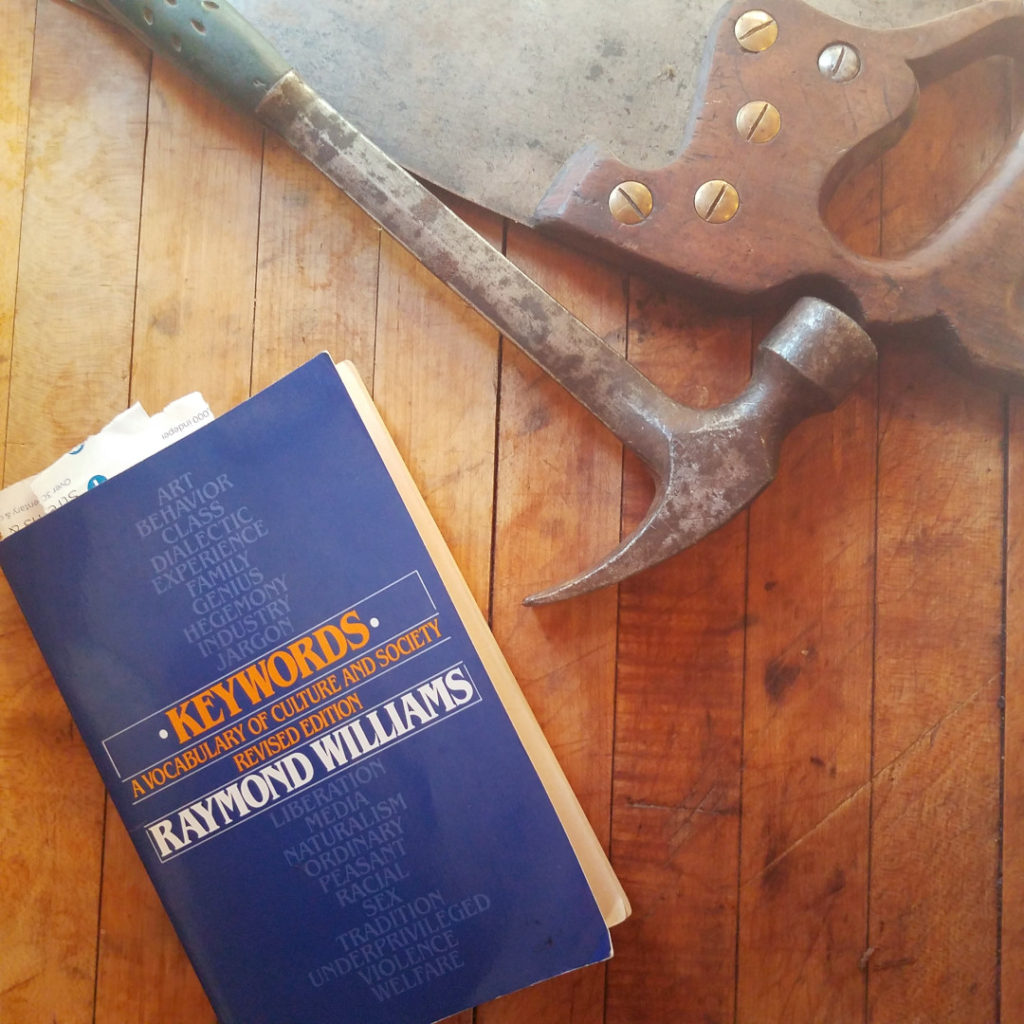

Raymond Williams called words like these “keywords.” Such words are in common circulation but hide a lot of depth. They are words that are thick with assumptions, and therefore contain how people think and talk about the world. Williams wrote a wonderful book tracing the history of about one hundred of these words, including labor.2Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (London: Fontana, 1988). http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/32043010

The story of the word labor is interesting. It started out in Old French and Latin as a concrete description of a hard task– carrying a heavy load on muddy path– and arrived in English with a well-established association between work and pain. From the 14th century to the 17th century the pain usage fell away (except for the word’s use to describe childbirth) leaving just the work meaning. The work it described, though, was usually difficult or unpleasant. It was similar to toil, which came from a root word meaning “to stir or crush,” and still has the the strong sense of suffering.

In the 18th century, philosophers and political economists like Adam Smith started using the word to describe the abstract quality of productive activity, as in “the cost of labor” or “the labor theory of value.” It became a technical term in the new science of economics. This abstract meaning also got a big boost from Marx in the 19th century. Along the way, the term additionally started to describe the class of people who did the work– the laborers became labor. So by the 20th century, the more concrete meanings had fallen into disuse. Officially, the association with suffering was long in the past, lost under measurements, polling data, movements, and everything attached to the more abstract meanings.

But that feeling of staggering and slipping, of carrying a heavy burden that you’d rather put down still hovers in the background. The idea that work is inherently arduous is deep-rooted. Think of the biblical story of the exile from Eden and the classical story of Sisyphus’s punishment of endlessly rolling a bolder.

What effect does this association between useful activity and pain have on how things are organized?

I’ve been noticing the effects of the association in my own life. If I’m not struggling with work, I get nervous that I’m doing something wrong. Or I catch myself thinking about things I don’t like to do as “real work” and any engaging activity as a form of goofing around.

There are bigger effects, too. In Bullshit Jobs, anthropologist David Graeber talks about the role this connection plays in making bad job situations seem natural.3David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs: A Theory, 2019. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1089773163

Lots of people have plenty of struggle hoisted on them without having to look for more, but I wonder if it’s harder to imagine fixing things if everyone assumes, at some level, that work is supposed to be miserable.

There’s more thinking to do here, but it looks like the misery<–>work association also functions with a work<–>virtue association. The work, misery, virtue triangle of associations reinforces an assumption that miserable work is somehow a good and necessary thing, which has many implications for individuals and the larger society.

But there’s also that activist association of labor as a class and a movement, which picks up a very different sense of struggle– the struggle against and the struggle for another world. There is still the heavy burden and plenty of slipping, but at least there’s an idea of putting it down.

References:

- 1“Labour | Labor, n.,” in OED Online (Oxford University Press), accessed February 15, 2021, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/104732.

- 2Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (London: Fontana, 1988). http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/32043010

- 3David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs: A Theory, 2019. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1089773163